- Dr. Jane Philpott, former Federal Health Minister and Markham–Stouffville MP, now chairs Ontario’s Primary Care Action Team.

- She says 6.5 million Canadians lack access to a family doctor or nurse practitioner.

- Without reliable primary care, many patients end up in hospital with advanced illnesses that could have been detected earlier.

- Ontario’s Primary Care Action Plan aims to ensure all residents have a family doctor or nurse practitioner by 2029.

- The plan includes creating 305 new or expanded primary care teams, backed by $1.8 billion in funding, to connect 2 million more Ontarians to care.

- Philpott says the long-term goal is to make primary care access as seamless and automatic as school enrolment.

Few Canadians have experienced the healthcare system from as many vantage points as Dr. Jane Philpott. From practicing medicine in rural West Africa to leading family medicine at Markham Stouffville Hospital, she has spent her career at the intersection of front-line care, medical education, and health policy.

Elected as Markham–Stouffville’s Member of Parliament in October 2015, Philpott served as Canada’s Minister of Health for nearly two years. The best selling author studied medicine at the University of Western Ontario, founded the Health for All Family Health Team in Markham, and helped shape the next generation of physicians as Dean of Health Sciences at Queen’s University.

Now tasked with steering the Ontario government’s Primary Care Action Team, Philpott is drawing on her decades of experience to address one of the most pressing challenges in healthcare today: ensuring every Ontarian has reliable and convenient access to a trusted family doctor.

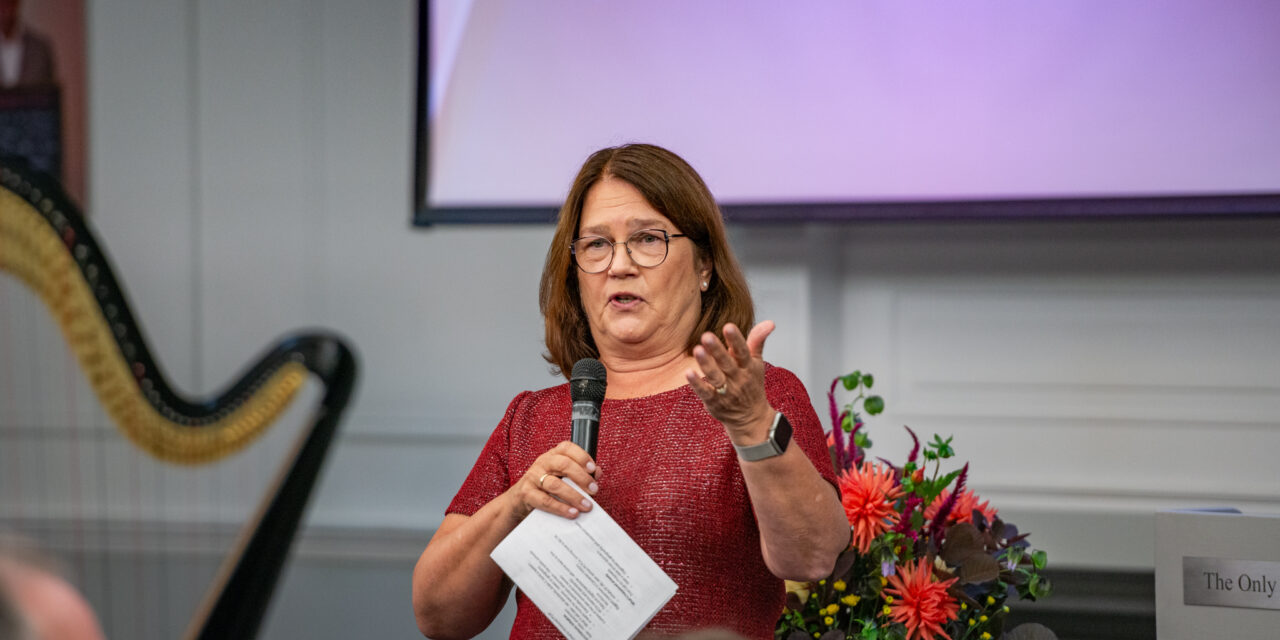

Philpott explored the topic during last week’s Parkview Services for Seniors 60th anniversary gala, where she was the keynote speaker. She recalled moving to Stouffville in 1998 and purchasing a home on Manitoba Road, which enabled her children to attend Summitview Public School. Enrolment, she noted, was a straightforward, almost automatic process, unlike the challenge many Ontarians face today in securing a family doctor.

“I did not have to beg to get my children into school. I did not have to put their names on a list and wait in hopes that someday they would get to go to school. I didn’t need to call all the important people in town to say, ‘Is there any way I could get my kids into school?’” she said.

At the time, two medical practices were serving a population of fewer than 20,000, and demand was being met. Nearly three decades later, Stouffville’s population has swelled to almost 60,000. While the number of schools has grown alongside that change, the supply of family doctors and medical practices has not.

School boards and the Province planned ahead to accommodate new students, Philpott noted, but the same foresight was never applied to healthcare. “Nobody ever organized primary care that way,” she explained. “In Stouffville, just like every other town in Ontario… access to primary care services, including family doctors, has not kept up with the pace of population growth.”

She pointed to the wider implications of the gap. “It’s a great thing that people are living longer now, but as they live longer, they need more healthcare services,” Philpott said. “It turns out it’s so bad that we have discovered… there are actually millions of people in this country that don’t have access to primary care.”

Canada’s publicly funded medicare system is a point of national pride, but it does not guarantee reliable access to care in every community, Philpott added. She cited figures showing approximately 6.5 million Canadians, including two million Ontarians, lack a family doctor or nurse practitioner they can rely on.

“We all thought that because we had a national health insurance system… we somehow had a national health system. It turns out we didn’t,” she remarked. “It turns out nobody had actually stopped and said every little community, every neighbourhood in the province, every neighbourhood in the country, should have a place to go as the front door to healthcare.”

Markham Stouffville Hospital remains an essential resource, but Philpott acknowledged that it should not serve as the first stop for people seeking medical care. Without access to a family doctor, patients lack the continuous oversight needed to monitor their health, undergo screenings, and catch problems early. Too often, she said, individuals arrive at hospital with advanced illness, limiting their options and worsening outcomes.

Philpott contrasted Canada’s approach with countries like Denmark, Norway, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands, where residents are guaranteed access to local primary care. There, clinics and service providers are organized within clear databases that help individuals and families find care without facing long waits. “This is what we need to do, but we’ve never done it before in Canada,” she said.

That realization inspired her national bestseller, Health For All, which called for a system organized geographically to fully support family doctors and ensure every community has access to primary care. The book caught the attention of Premier Doug Ford and his office, who asked Philpott to chair the newly formed Primary Care Action Team.

The Action Team’s mandate is ambitious: to ensure “100% of people in Ontario are attached to a family doctor or a primary care nurse practitioner working in a publicly funded team, where they receive ongoing, comprehensive, and convenient care.”

Philpott told Ford the plan would require a significant upfront investment. “It’s going to save us money in the end, because… if you diagnose conditions early on, if you prevent somebody from getting late stage cancer, it’s going to cost a lot less,” she explained. According to her, the Premier replied: “‘You tell me what you need and you can go fix the problem. I don’t want a report on my desk, I want you to go fix the problem.’”

The resulting Primary Care Action Plan is built around three pillars. The first is about making sure more people are connected to a primary care team, with clear standards for what patients can expect. The second focuses on convenience, with new digital tools to help patients book appointments, access records, and navigate the system more easily. The third is about supporting providers, including recruiting and retaining doctors and nurse practitioners, reducing paperwork, and expanding teaching clinics.

Ontario is now investing more than $1.8 billion through 2029 to make the Action Plan a reality. The first year alone aims to see 76 new primary care teams formed or expanded, connecting 300,000 underserved Ontarians. By 2029, the target is 305 teams and more than two million additional residents attached to primary care.

At its core, Philpott explained, the concept is simple: everyone should have continuous, comprehensive care, ideally from a family doctor but also from nurse practitioners, who can provide lifelong support. “And we know for sure that countries and regions and cities, in towns that do this and do it well, they actually get better health outcomes at lower costs in a way that is both fair and accessible,” she said.

The Action Team’s work also includes tackling Ontario’s Health Care Connect waitlist, which was created to help match people to general physicians. “It had 235,000 people that signed up to a digital waitlist that wasn’t adequately being attended to,” Philpott said. “We have cleared 42 percent of that wait list. 98,000 people have been matched to a family doctor since we started our work.”

Legislative reform has been another important element of the Action Team’s mandate. They introduced new legislation in May requiring a system-wide approach to primary care across Ontario. The law, which passed in June, is grounded in six principles: it must be universal, connected to broader health and social services, convenient, supported by strong electronic records, equitable and inclusive, and accountable through annual public reporting.

“It is now the law of the land. So this government, and every future government of this province, has to develop a primary care system that meets those six objectives,” Philpott said, outlining her long-term vision for healthcare access that is as seamless as school enrolment.

“We will eventually get to a place that is as automatic as when you move to a new community and know for sure your child will have a school to attend,” she concluded. “When you move to that community, you will also know there will be a place where you can get primary care. And we have until 2029 to get that done.”